Category Uncategorized

istanbul, social media, and the right to the city

Being called the Turkish Summer, both Right to the City theorists and activists have begun to argue that what has occurred in Istanbul and across many parts of Turkey is a classic example of how individuals within organized groups have the power to reclaim and redefine the processes of how cities are developed and governed.

At the center of this protest movement is a new urban development being proposed at Taksim which would essentially demolish one of the largest open public green spaces located in central Istanbul through the reconstruction of an historic army barracks which would include a new shopping mall located inside. Massive demonstrations have erupted against both the project and the resulting heavy handed response by the state. (For those of you living in Richmond, Virginia, this contention against the development could be compared to the ‘Ballpark in the Bottom‘ project located in Shockoe Bottom).

This event represents the importance of one of the most fundamental pillars of urban planning and development, Civic/Public Participation. People of Istanbul are reclaiming their ‘right to the city’ and how it will be developed/governed. Under the guidance of some progressive Turkish urban planners along with activists and scholars, protesters since the beginning of the project are expressing their anger towards how the government has approached its planning practices which has historically neglected public participation. Turkey’s lack of public participation through traditional government level urban planning does not simply create weak and unpopular planning projects but has fermented into an all out insurrection of the masses of the people against the Turkish government and planning departments. Although police violence has been what has escalated some of the protests, poor urban planning policy from governmental officials is at the protest’s heart.

The struggle to reclaim space within Istanbul’s Gezi Parkı/Taksim Square can be defined as ‘a cry and a demand’ for a renewed sense of urban space and life. This method of reclaiming a renewed space in the city comes out of the work from French Philosopher Henri Lefebvre who in 1968 coined the term the “Right to the City” as a way of explaining these types of protest movements.

The term the ‘Right to the City’ (RttC) was first developed by Lefebvre during Parisian uprisings in 1968 (Kuymulu 2013) where he argued that civic protests are groups of individuals acting to demand their right to certain aspects of the city through ‘a cry or demand’. Harvey (2003) takes this argument a step further saying that not only do people have a right to access various parts of the city, but they also possess ‘a right to change it’ (Harvey, 2003; 939).

Information Communication Technologies (ICT/ICTs; a.k.a. social media) are often discussed in understanding the impact on social organizing and changing dynamics of social movements and community organizing. The rise of social media and networking ICTs across the ‘urban digital skin’ within our cities are specifically cited as tools to help develop the capacity for social movements to grow and affect change (Garrett 2006, Rabari 2013). The case of Istanbul’s protest is an excellent example of this ICT enabled social movement.

The Right to the City theorists argues that mobilizations arise in an effort against new forms of ‘neoliberal urbanization’ (Türkmen 2011, Uitermark et al. 2012, Ergn 2006). Türkmen argues that these typically take the form of the people protesting neoliberalism and argues that Istanbul in particular is a place that illustrates this struggle against neoliberal development. Ergin documents the local inhabitant’s struggle against urban renewal projects in Güzeltepe, Istanbul that had developed into a form of ‘gecekondu resistance’ to protect the gecekondu housing structures. This illustrates that local inhabitants begin to employ their struggle of demanding improvements and a change in urban governance and the development within their city.

People are demanding or crying for ‘the right to the city’ and a ‘renewed right to urban life’ through creating spaces of ‘experimental urban utopias’ (Lefebvre 1996).

These spaces become sacred spaces where individuals and groups are able to create their own versions of what they feel is the correct form of and experience with the city in the effort of contesting urban space. This elated feeling can be illustrated from people’s descriptions directly from these spaces. Catterall (2013) discusses the recent Turkish Experience of the Gezi Park protests as being a similar utopia space. He quotes his colleague describing the protest scene saying “there is a sense of wonder when one beholds an event of this kind. New insight is developed through the energies (of people) being so close together. There is a transformation thinking and a change of consciousness” (Catterall 2013, p. 420).

Where did the protesters come from?

For over several months, Turkish civil society has been in an uproar over the proposed construction project on Istanbul’s Gezi Park near Taksim Square. This development in particular can be an example the neoliberal development projects discussed earlier. But this mobilization did not just suddenly arise. I argue that there has been years of civil organizations and engagement occurring in Istanbul for several years and developed into the massive uprising we have seen today.

Academics and RttC practitioners have recognized for some time that Istanbul has been developing the required revolutionary momentum for several years (Ergn 2006, Türkmen 2011). Hoyng (2012) documents the participatory framework that was developed during the Istanbul 2010: European Capital of Culture event. During the time leading up to ‘Istanbul 2010’, a unique ‘place making ‘participatory technique/framework was developed that was focused on engaging people at the neighborhood level to organize together to showcase Istanbul’s unique culture.

Istanbul has a unique neighborhood level culture, known in Turkish as mahalle kültürü. This allowed for an easier proliferation of a new ‘networked governance’. The hope was that this participatory framework would begin to establish a compounding network of networks that would build off of one another. This would develop into the aforementioned ‘network governance’ though the ‘expanding network of self-organizing’. Istanbul 2010 organizers believed that this type of framework, enhanced by social networking technologies, would become ‘a model for the world’ and would showcase the true cultural icons within Istanbul. All of what would be showcased would be developed from the people.

Hoyng even describes the revolutionary potential for this type of participatory framework that alludes to a pending culture of protest and a people’s revolution. Hoyng states that:

“While Networking in urban governance generates particular modalities of participation in and belonging to the creative city, it also enables modalities of staging protest and struggle over urban transformation and the project of the creative city. As I will suggest, possibilities for resistance reside in those forms of engagement and productivity that elaborate transformations and differentiation beyond control.”

This is a very powerful statement and analysis of the revolutionary potential of this form of networked governance. Noting that this publication came out before the massive Gezi Parkı/Taksim Square ‘Turkish Summer’ protests is important to understand the revolutionary potential this form of participatory framework holds.

The Istanbul 2010 participatory model established a framework that was able to bypass traditional forms of identity politics (Hoyng 2012). Being an inhabitant of an area or political body defined participation. Furthermore, one’s level of participation within this participatory paradigm defined their authority or overall ‘level of participation’. Hoyng developed the term ‘Popping up and Fading Out’ to illustrate this practice. Hoyng points out the inherent participatory dimensions of Information Communication Technology (ICT) enabled social networks illustrating that “participatory subjects ‘pop up’ (when using the ICTs) and then ‘fade out’ (when not using the ICTs), after which they have no visible presence.”

The Istanbul 2010 participatory model established a framework that was able to bypass traditional forms of identity politics (Hoyng 2012). Being an inhabitant of an area or political body defined participation. Furthermore, one’s level of participation within this participatory paradigm defined their authority. Hoyng developed the term ‘Popping up and Fading Out’ to illustrate this practice.

Hoyng points out the inherent participatory dimensions of ICT enabled social networks illustrating that “participatory subjects ‘pop up’ (when using the ICTs) and then ‘fade out’ (when not using the ICTs), after which they have no visible presence.” (2012; p. 13).

Iveson (2013) illustrates that we are re-framing where decisions are being made towards a “radical form of enfranchisement” (2013, p. 945). This change in where and who can participate in democracy is a shift away from traditional identity politics that dominates decision making processes in society. ICT enabled civic engagement has redefined key aspects of democracy and who can participate.

But, is the Turkish political establishment (including current urban planning practitioners) a part of this new political paradigm?

During the first weeks of the protests, Turkey’s Prime Minister Tayyip Erdoğan referred to Twitter as a ‘Pest’ and said, “The thing that is called social media is the biggest trouble for society right now.” This is a clear illustration showing how Turkey’s political leadership is completely unaware and unwilling to participate in this new age of democracy and civic engagement. It is imperative that the current momentum of civic participation be captured and implanted into the mechanisms of urban planning within the Turkish government.

Social media has been at the core medium of communication during the protests. Facebook groups, Twitter feeds, and images of police violence have galvanized a message of solidarity against the government both within Turkey and across the world. But the revolutionary spirit of the Turkish population isn’t an isolated case but rather is the nature of our historical moment across the world. This internationalization of local struggle is known as ‘Glocalism’. The term Glocalism refers to the capacity for social movements to be able to frame global struggles into the local context and vice versa (Wallin & Horelli 2012). Framing the struggle through a Glocal lens allows for local social movements and struggles to be framed and connected with similar struggles across the globe. Furthermore, community networks are able to build stronger networks when connected to global context (De Cindio & Schuler 2012).

A new age of governance is emerging in recent years which embraces new democratic elements that are an innate product of these new media outlets. These outlets help to facilitate and challenges against existing power structures through the massive exchange and collaboration of people and ideas.

Urban planners have a strong desire for civic participation but are many times unsuccessful in capturing participation from the public using traditional methods of engagement. Today, Turkey has a truly amazing opportunity to seize the unprecedented level of civic engagement to improve it’s urban planning practices and develop a truly democratic politic. As a result from the protests against the Gezi Park project, people from all walks of Turkish society are becoming active participants in the urban planning process.

Without any political leadership capturing this social momentum, Turkey will lose a great opportunity of institutionalizing strong and progressive planning practices.

Separated Cycle Paths: Who Asks the Cyclists?

In the discussion about separate or “protected” cycle tracks, it has been surprising that planners and decision makers don’t seem to want input from those who actually ride bikes.

In some cases, there is open disdain for those who have been cycling in North America for many years. Now that cycling is becoming popular, largely through the example and tireless efforts of these cyclists, we are labeled “a frustrating deterrent to mainstreaming cycling” on the popular “Copenhagenize” blog. The author even suggests that we hit our children, and insinuates that we prefer to mix with cars and trucks on freeways rather than ride on a separate path. (We don’t, the photo in the blog shows a location where a cyclepath actually makes sense.)

Those are extremes, but the tenor isn’t much different when you talk to many bicycle advocacy groups who have jumped onto the cycle path bandwagon.

Why…

View original post 1,191 more words

Cycling fatality on Memorial Drive and Houston’s need for Bicycle Infrastructure; A call to action

On the evening of Monday August 12th 2013, a cyclist was struck and killed by a motorist on the 6700 block of Memorial Drive in Houston, Texas. This is a tragic accident that took place illustrates the NEED for the City of Houston to take the implementation of Safe Bicycle Infrastructure across the city seriously.

Below is an image via Google Street-View of what Memorial Drive looks like near the location the accident that took place. There are three lanes of traffic in each direction with no area for cyclists to ride. The granite path on the right is a popular running trail dedicated to pedestrians. As you can see in the image, cyclists don’t have much room to ride safely with out coming within a safe passing distance of a motorist driving in the same lane.

Recently, the city of Houston passed a ‘Safe Passing’ ordinance requiring motorists to provide at least 3 feet between the vehicle and the cyclist when passing. Although this is shows the city is willing to promote bicycling safety though ‘quasi-judicial’ means, the city must take the next step and make the implementation of safe cycling infrastructure a number one priority.

Below is an image I took of an example of a dedicated bicycle lane in Copenhagen, Denmark. The creation of grade separated, elevated/dedicated lanes allow cyclists to have both a separate path to travel and also a physical separation between them and the motorists. There is no reason why the City of Houston cannot have similar styles of cycling infrastructure for people to more safely ride.

Memorial Drive has more than enough space in which the city can build dedicated bicycle lanes in each direction (such as is pictured below). If the city took cycling safety infrastructure seriously, tragedies such as what happened earlier this evening may not have taken place.

Dream9 Released; Setting a Legal Precedence

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Article 13. Section (2):

“Everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country”

According to many sources, members of the Dream9 group have been released from custody where they were held for several days in a privately owned Immigrant Detention Center in Arizona.

The question is does this set a legal precedence for international travel for those who are undocumented living in the United States. Currently, undocumented persons cannot travel internationally and be allowed to re-enter. But, with the events that are currently unfolding involving the #Dream9, this legal statute is being directly challenged and a new legal/administrative stature could be established.

Walking Down The Street; Poetic Expression from Istanbul and What To Do with Urban Form in the United States

WALKING DOWN THE STREET by: Orhan Veli Kanık

Walking down the street,

I realize that I’m smiling.

And I smile even more

because I’m thinking

passers-by must think me

a bit funny in the head –

or, of course, that I’ve been drinking…

Walking through the streets of Istanbul is an amazing feeling. Cafe’s literally spill into the narrow streets, so overcrowded with dinner parties it becomes almost impossible to walk though.

The image presented below is just one example of a typical street in Istanbul where cafes, bars, and restaurants litter the urban landscape creating an extremely unique and welcoming aroma of joy and festivity. This image is of the Nevizade section located near Istikal Street close to Taksim in the center of Istnabul.

Why not have this image be of here in Richmond, VA or Houston, TX? A recent article publish by The Daily Beast, ranked Richmond the 7th most ‘Aspirational City’ in the United States. Taking some of the wonderful things that Istanbul has to offer such as its open street cafe culture and implementing them to areas of the city seeking revitalization is just one way the City of Richmond can use it’s ‘aspirational’ status to improve the urban landscape.

Recently the city of Richmond passed an ordinance allowing temporary patio dining in certain parts of the city (although the ordinance is still quite restricting). Richmond’s alleyways also offer excellent opportunities where the city can introduce a network of Istanbullu cafe scenes. Furthermore, the city is currently looking for proposals on what to do with the old 17th St. Farmer’s Market site in Shockoe Bottom which could potential be a great place for cafes and on street dining.

In my hometown of Houston, Texas, where advocacy towards pedestrianization of the urban environment is on the rise, could also look to Istanbul for inspiration. In the same Daily Beast article mentioned above, Houston, Texas ranked #3 as the nation’s most ‘aspirational’ city just behind the cities of Austin and New Orleans. With all these cities located next to one another some may call this part of the country the ‘Aspirational Corridor’.

In the past few weeks, there has been a call for establishing parts of the City of Houston as ‘car-free’ specifically in the Downtown Main Street corridor. Istanbul again could serve as a model in how the city should approach and design parts of the city to be car free or car-lite.

The final image below is of Istikal Street in Istanbul. One of the most pedestrian friendly avenues in Istanbul and a favorite place to gather for all Istanbullus. This street is very similar to what other large urban cities have across the world such as Mexico City, D.F.’s Madero Street which was recently converted into a pedestrian only avenue. The bottom most image is of me in Mexico City’s Madero Street. With some planning, this too may be what Downtown Houston’s Main Street Pedestrian corridor will soon look like…..

New BART passenger rail cars have been unveiled.

The San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) system has unveiled its newest train series for people to see. These remarkable trains appear to be some of the ‘slickest’ train cars I have seen in many years.

Although BART has had some trouble recently in what many claim to be inequitable treatment towards their workers, this project shows a renewed interest in the United States’ effort towards re-investment in the country’s week public transportation infrastructure. Leading the world in design, this project will bring renewed attention towards Public Transit for the nation.

(Photo courtesy of ALICIA TROST/ http://www.dailycal.org/2013/07/24/bart-opens-new-train-designs-to-public-viewing/ )

THE TRAM-DRIVER…

THE TRAM-DRIVER…

By: Orhan Veli Kanık

He looks in front of him all the time.

He doesn’t smoke.

He is

a wonder!

The tram drivers of Istanbul have a unique position within the tumultuous streets of Istanbul. The path the trams take is used by not only the tram, but also by cars, pedestrians, large 18-wheelers, riot patrol police, water cannon tanks, you name it…

Below are some photographs of such tram drivers and the beautiful trains/buses they conduct.

The final image is of a police officer. City buses haves been used by security forces as mobile home units. The police officers have been forced by their superiors to sleep in and essentially live out of these units during the ongoing demonstrations.

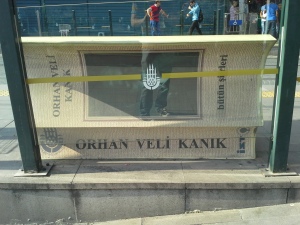

Civic Art, Public Transport, İstanbul, and Orhan Veli Kanık

İstanbul is a very unique city that has a strong sentiment of civic pride. This can be seen in some of the creative infrastructure installments the city has placed across the city. The image below is a bench in the shape of a book located at the T1 tram stop of Sultanahmet that is dedicated to one of İstanbul’s most famous and respected poets of the 20th century, Orhan Veli Kanık whose poem There Must be a Catch was featured in an earlier post.

Illustrating the significance of this poet on the literary landscape, some literary critics and scholars argue that Orhan Veli Should have been Turkey’s first literary Nobel Laureate. The first to receive the honor was ‘the other Orhan’, Orhan Pamuk, who was honored with the award in 2006 for his masterful novels with themes like life, love, and İstanbul.

Everything You Always Wanted to Know About What’s Going on in Istanbul * But Were afraid to Ask — (Part 1)

As many of you all have heard recently about Istanbul in the last several weeks, there has been a large protest movement that began in Taksim Square . But, what many people may be unaware of is this movement began as a reaction against the development of a shopping mall designated to be built on Gezi Park, located alongside Istanbul’s Taksim Square.

Below is a recent publication by the Turkish 2006 Nobel Laureate writer Orhan Pamuk describing his experience concerning the recent protests:

In order to make sense of the protests in Taksim Square, in Istanbul, this week, and to understand those brave people who are out on the street, fighting against the police and choking on tear gas, I’d like to share a personal story. In my memoir, “Istanbul,” I wrote about how my whole family used to live in the flats that made up the Pamuk apartment block, in Nişantaşı. In front of this building stood a fifty-year-old chestnut tree, which is thankfully still there. In 1957, the municipality decided to cut the tree down in order to widen the street. The presumptuous bureaucrats and authoritarian governors ignored the neighborhood’s opposition. When the time came for the tree to be cut down, our family spent the whole day and night out on the street, taking turns guarding it. In this way, we not only protected our tree but also created a shared memory, which the whole family still looks back on with pleasure, and which binds us all together.

Today, Taksim Square is Istanbul’s chestnut tree. I’ve been living in Istanbul for sixty years, and I cannot imagine that there is a single inhabitant of this city who does not have at least one memory connected to Taksim Square. In the nineteen-thirties, the old artillery barracks, which the government now wants to convert into a shopping mall, contained a small football stadium that hosted official matches. The famous club Taksim Gazino, which was the center of Istanbul night life in the nineteen-forties and fifties, stood on a corner of Gezi Park. Later, buildings were demolished, trees were cut down, new trees were planted, and a row of shops and Istanbul’s most famous art gallery were set up along one side of the park. In the nineteen-sixties, I used to dream of becoming a painter and displaying my work at this gallery. In the seventies, the square was home to enthusiastic celebrations of Labor Day, led by leftist trade unions and N.G.O.s; for a time, I took part in these gatherings. (In 1977, forty-two people were killed in an outburst of provoked violence and the chaos that followed.) In my youth, I watched with curiosity and pleasure as all manner of political parties—right wing and left wing, nationalists, conservatives, socialists, and social democrats—held rallies in Taksim.

This year, the government banned Labor Day celebrations in the square. As for the barracks, everyone in Istanbul knew that they were going to end up as a shopping mall in the only green space left in the city center. Making such significant changes to a square and a park that cradle the memories of millions without consulting the people of Istanbul first was a grave mistake by the Erdoğan Administration. This insensitive attitude clearly reflects the government’s drift toward authoritarianism. (Turkey’s human-rights record is now worse than it has been in a decade.) But it fills me with hope and confidence to see that the people of Istanbul will not relinquish their right to hold political demonstrations in Taksim Square—or relinquish their memories—without a fight.

The heart of this issue shows the importance (and necessity) of community involvement in Urban Planning for both successful implementation of development projects and a nation’s functioning democracy.

I was fortunate enough to visit Gezi Park where thousands of people had established a large protest camp for several weeks before bulldozers had destroyed a large portion of it. This was done through the forceful removal of the protestors by police using chemical water cannons and American made tear gas. What I witnessed while visiting the park during the peaceful occupation was nothing short of remarkable. An atmosphere of joyful independence and festivity filled the air. During this period, Gezi Park had become the ‘center of the universe’ for the international/global revolutionary movement.

What followed was the forceful removal of this camp by the police under the direct orders of the Prime Minister Tayyip Erdoğan. What had developed from several weeks of peaceful public protest and organization, the Gezi Park peace camp was completely leveled and is now currently under police occupation. (Many jokingly remark that the police now get to enjoy the park while everyone else is forbidden entry).

While it may seem simple to place blame on the police force for the cruelty and violence against the protestors, the police themselves have become victims of the Prime Minister’s unyielding force. Police officers and agents have been forced to work and live under extremely harsh conditions during the state’s effort to maintain ‘control’. When walking around Istanbul there are busses scattered around the city filled with exhausted officers attempting to catch a few minutes of sleep before their commanding officers force them back to duty.

At least 4 police officers have committed suicide due to such harsh conditions.

I’ll be posting more information concerning all this Istanbul soon inclusion some poetry and more about the protests soon. Keep posted!